The News Lens

Trump’s Unlikely Ally: The Chinese Dissident

By: Edward White

|

Why you need to know

A high-profile Chinese dissident sees U.S. President-elect Donald Trump as a potential game changer for human rights in China.

|

This March, Donald J. Trump, then standing to become the Republican presidential nominee, drew the ire of three prominent Chinese dissidents after referring to the 1989 Tiananmen Square Massacre as a “riot,” and praising the “strength” shown by the Chinese government in suppressing the protests.

“Trump’s callous dismissal of the tragedy, and his apparent esteem for Beijing’s butchers, left us speechless, in pain and in tears,” wrote Yang Jianli (楊建利), Fang Zheng (方政) and Zhou Fengsuo (周鋒鎖) in a Washington Post op-ed.

While Trump’s comment on Tiananmen has probably been largely forgotten by many, swept up in the torrent of Tweets and soundbites flowing from the mouth and fingers of the next U.S. president, Yang still wants an apology for the careless misrepresentation of the peaceful protests and violent crackdown. Surprisingly, however, the man who spent five years in a Chinese prison says Trump has shown signs that his presidency may help advance democracy and human rights in China.

“According to his recent moves, I am more optimistic than I used to be,” Yang told The News Lens International in Taipei.

Those “moves” include Trump’s historic phone call with Taiwan President Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文), his open questioning of the sanctity of the so-called “one China” principle and his comments after the death of Cuban dictator Fidel Castro.

“When Castro died, [President] Obama dared not to even call Castro what he was – a dictator. Trump came out and said the right thing,” Yang says.

Notwithstanding Trump has “never talked about the universal value of human rights,” Yang believes Trump’s team has signaled the issue may form part of the new administration’s foreign policy platform.

“His team had to justify what he did [in talking to Tsai] by ‘values,'” Yang says. “The justification they came up with was ‘democracy,’ and ‘shared values’ and ‘[Tsai] is a democratically elected leader.’ That is why I’m optimistic.”

Trump’s 10-minute conversation with Tsai was the first time a president or president-elect of the United States directly contacted the leader of Taiwan in 40 years. His somewhat defensive statements that followed, questioning why the U.S. had to be “bound by a one-China policy,” likewise broke decades of protocol.

For Yang, one of the world’s preeminent critics of China’s authoritative regime, U.S. support for democracy and human rights has long been displaced by a focus on business ties. The president-elect’s apparent brashness in the face of tradition provides a rare opening.

“If Trump wants to change the equilibrium that has existed for 40 years, to have a new approach to China and Taiwan, I think there is an opportunity for the human rights issue, which concerns the core values of democracy, to be elevated to be a very important part of Trump’s foreign policy.”

Yang, once considered a “rising star” in the Communist Party, left China in the 1980s to study mathematics at Berkeley. In 1989, the then 26-year-old returned to Beijing, in time to witness firsthand the massacre at Tiananmen Square, Beijing. He went on to study political economy at Harvard and refocused his energy on promoting democracy in China. In 2002, Yang once again returned to China, this time undercover, in a bid to support the labor movement. He was arrested upon arrival and held in detention for two years before being convicted of spying in 2004 and sentenced to five years for espionage and illegal entry.

Yang’s arrest and detainment sparked an international outcry. Lobbying efforts from the United States went on for years and included bipartisan support from U.S. lawmakers and the United Nations, in addition to human rights organizations.

“A good part of the five years [in jail], nearly 15 months, I was kept in solitary confinement,” he says. “There was an outpouring of support for me but at that time I was kept in solitary confinement, I didn’t know. When I first had a visit from my lawyer in prison, I found that out.”

He believes his “relatively short” sentence and early release in August 2007 shows that international lobbying on human rights issues can have an impact on decision makers in Beijing.

“Without the pressure from the U.S. and other democracies, international rights groups, I may still be languishing in a Chinese prison,” he says.

The problem is that his case, notwithstanding and a few others like it, has become an exception. Yang says that in the past 10 years since he was released, rarely has the U.S. pursued human rights cases “openly, publicly, directly, to the Chinese government.”

Meanwhile, the situation faced by people who oppose the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is worse than when he was in prison.

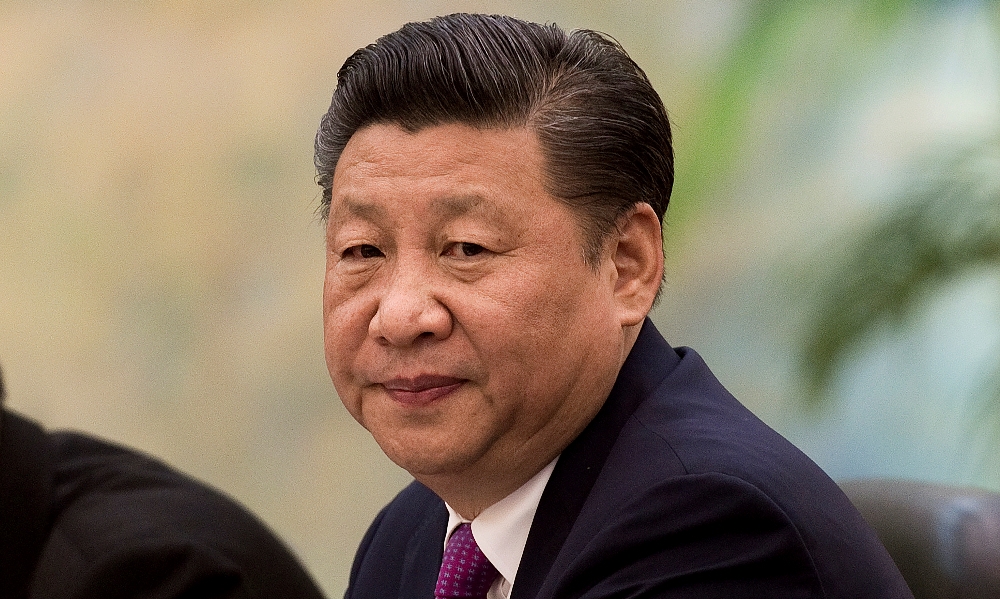

“Look at what has happened in the past 20 years: the U.S. has delinked traded from human rights,” he says. “We all know after [President] Xi Jinping (習近平) assumed power [in 2012], he intensified the crackdown on civil society, tightened up the flow of information, and tightened up control over almost every aspect of peoples’ lives,” Yang says.

He points to recent “show trials” in China where human rights lawyers have been forced to confess to alleged offenses on public television.Several of the hundreds of human rights lawyers and supporters detained as part of last year’s 709 Crackdown were released on bail or given lighter sentences after confessing on public television to subverting state power.

“That is a practice that has not been used for many, many years – after the Cultural Revolution,” he says. “Both domestically and internationally, the situation is worse.”

Reports have emerged this week that nine people involved in land protests in September in Wukan, southern China, have been sentenced to up to 10 years in jail. The village was formerly known as a potential model for democratic activities in China.

This September, Human Rights Watch’s China director Sophie Richardson noted many governments privately lament “a lack of leverage” when it comes to Beijing’s human rights abuses. Yang suggests the loss of confidence on the part of the international community, including the United States, is borne out of a fear of reprisal from Beijing.

“Even in the U.S., I can give you many examples of how the democracy has been affected by China’s engagement and buying power,” Yang says. “I have worked with so many professors, they are so afraid of China; to the point they cannot be critical of whatever China does.”

China, Yang believes, is bluffing.

“I am proof it is a myth that if the U.S. took a stronger chance on human rights issues with China that the Chinese would respond harshly with retaliatory actions like military power, or closing off its market and things like that. It has never happened,” he says.

He points to Norway and China. On Dec. 19, the two countries announced a resumption of diplomatic relations six years after China cooled ties following the award of a Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo (劉曉波), an imprisoned democracy advocate. Yang was at the Nobel ceremony in Oslo on Dec. 10, 2010, where Liu was represented by an empty chair. While the restart of official ties is anticipated to assist Norway’s bid to win a free-trade deal with China and benefit the country’s exports volumes, Yang suggests that business resumed much earlier than many acknowledge.

“Four days after the award ceremony, Dec. 14, 2010, China’s state-owned oil company struck a big deal with the Norwegian oil company and everything continued,” he says. “I always try to tell those policy makers that economic growth for China is probably the single reliable source for legitimacy for CCP continued rule. So they won’t want to jeopardize that.”

|

|

Yang Jianli hugs his wife Christina Fu as he speaks to reporters on Capitol Hill in Washington August 21, 2007. The Boston-based Chinese democracy campaigner returned home after serving five years in a Chinese prison for stealing into the country and spying for Taiwan. REUTERS/Kevin Lamarque

|

Hit them where it hurts

Almost 10 years after his release from prison, Yang continues to devote much of his time advocating for democracy in China. Today, his bright eyes are accentuated by a small pair of circle eye glasses, of the same ilk worn by fellow political activist Mohandas Gandhi and later John Lennon. The range of his voice, even when he speaks English, seems to flow through the different tones of his native language, especially as he gets passionate about a particular point, and almost always when he talks about Xi Jinping. While it is certainly conceivable Yang will never again step foot in China, he still refers to the country as “back home.”

Yang, interviewed in Taipei’s busy Ximen district on a crisp late afternoon in early winter, is promoting his latest new position paper, which proposes the Trump administration “strikes” directly at the vulnerable spots of the CCP to enable a democratic transition in China.

Given that economic growth is perceived as a key source of legitimacy for China’s ruling party, a central part of Yang’s proposal is to target China’s economy by using the U.S. market as leverage. He wants Trump to: threaten to withdraw China’s permanent trade status unless serious improvements are made in the areas of human rights, political reform, and de-militarization of the South and East China Seas; deny foreign tax credits to companies that invest in Chinese localities with gross human rights violations; and ban imports from those areas.

In a somewhat Trump-esque line, Yang also suggests “other similar measures to address the unfairness of one-way free trade that is resulting in China’s huge trade surplus of US$3 trillion with the resulting loss of millions of American jobs.”

Yang’s ultimate aim is to empower citizens to, “come up with a viable democratic opposition to push forth a peaceful transition to democracy.” However, not all of his underlying assertions are shared by other China watchers; namely that Chinese freedoms are in fact regressing, and that achieving Western-style democracy is high on the agenda for ordinary Chinese people.

In an interview in August with the highly-respected Sinica Podcast, Cheng Li (李成), a distinguished U.S.-based academic and writer on China with the Brookings Institution, noted that no country has been able transition to a rule of law in a matter of years.

“This is not fair to China. We can ask, ‘How many years or decades for the United States to really make a transition to a constitutional rule of law country?’ For the U.K. it was really several centuries, in the United States, many decades.”

Asked directly whether China was progressing to be a country governed by rule of law, despite the fact that journalists and lawyers continue to be imprisoned and censored, he said, “Absolutely.”

Andy Rothman is an investment strategist at Asia-focused U.S. investment firm Matthews Asia and was a longtime China-based analyst. In an October interview with the same podcast, he suggested that economics and personal freedom, not democracy, was at the “top of the list” for Chinese people.

“I think we have to be careful not to superimpose our own framework for what makes us happy and content on that of Chinese people,” Rothman said. “The idea that they want to overthrow their government because they don’t have the ability to go to the polls soon and vote for a Chinese version of Donald Trump as Hillary Clinton is not realistic.”

Rothman gave the caveat that in the long-term China’s rapidly growing middle class will likely become increasingly concerned with local government spending, accountability and the input of citizens, as well as the environment and education.

“These are definitely factors that are going to be increasingly important over the coming decades but not something that I think is a significant risk if you are thinking about the next five to 10 years.”

Yang acknowledges Rothman’s view “contains some truth.”

“People may not think democracy is that urgent in China. That may be true. Especially for those who are part of the ruling structure. But if you frame your question this way: ‘If tomorrow when you wake up there will be democracy in China.’ They say, ‘That would be great.'”

Yang believes it is the process by which democracy may be achieved that worries Chinese people.

“This process can be very unpredictable. The elite, the middle-class people in China may be afraid of that,” he says. “Maybe they are not in favor of this kind of situation.”

Outside of economic growth, Yang considers political and social stability as the other key source of legitimacy for the CCP. He accepts that if the CCP was challenged domestically the Chinese leadership may use military actions to drum up nationalism to reinforce its control over the population.

“There is always a risk that when the regime is forced into a corner, for one reason or another, it may use all kinds of measures to mobilize nationalist sentiment to its advantage,” he says. “That includes military action, clashing with neighboring countries, especially Taiwan. That is always a danger, so that is something we are really cautious about.”

The position paper further suggests the U.S. use Taiwan as “leverage” and calls on the U.S. to “modify the Taiwan Act and the Six Assurances to reflect a full democratic country status and affirm its legitimacy by allowing Taiwan to be a normal member of the international community.”

While he acknowledges the implication of the term “leverage,” he maintains Taiwan and the U.S. are currently aligned in their strategic interest. Right now, he says, Taiwan has great value to help China and become a full democracy.

“I think the most dangerous situation is if Taiwan loses such value. [If] the U.S. and other democracies do not see there is big value in Taiwan to have strategic leverage, it is a dangerous situation.”

If, however, Taiwan and the U.S. remain aligned, Yang is confident China is unlikely to pursue military action across the Taiwan Strait.

“We all know China has been bluffing on its military strength. Xi Jinping has taken tremendous effort, trying to reform the military, to restructure it, at the same time he revealed to the people – to the surprise of many – how corrupt the military was, or even is today,” he says. “I don’t think the Chinese military has the necessary capacity to prevail in any military clash with any neighboring country, especially when the U.S gets involved.”

Further, a Chinese defeat may trigger an opposition challenge to the CCP, possibly from nationalists within China, he says.

“That, combined with a democratic opposition, can topple the regime. I think Xi Jinping understands that better than I do, that it is not easy to do so.”

An inconvenient problem

In the weeks since the U.S. election, a handful of individuals and Washington’s think tanks with ties to Taiwan have been linked to Trump. The list includes: incoming chief of staff Reince Priebus; Stephen Yates, a deputy national security adviser to former vice president Dick Cheney, who visited Taiwan earlier this month and met with President Tsai; the Heritage Foundation and its founder Edwin Feulner; and, former presidential candidate Bob Dole and the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC) he founded. A host of other think tanks are understood to be supportive of Trump’s emerging Asia policy, if it can be called that, including American Enterprise Institute (AEI), Center for Chinese Strategy at the Hudson Institute and the Project 2049 Institute.

U.S. President Barrack Obama, at a press conference in Washington on Dec. 16, was asked whether the U.S. policy on China-Taiwan relations needed “a fresh set of eyes” or if “unorthodox approaches” could put the U.S. on a “collision course” with China. Obama said he was “somewhere in between,” noting both the benefits of “new perspectives,” but also cautioning the incoming administration it is important to have “all the information” before changing the country’s foreign policy direction.

Politically, many of those Taiwan-friendly names and organizations linked to Trump have been somewhat in the wilderness for years. This has reinforced some fears that the U.S. president-elect, already considered something of a wildcard, may sway from the balance of power that has ultimately ensured peace in the region.

As Obama said, “That status quo, although not completely satisfactory to any of the parties involved, has kept the peace and allowed the Taiwanese to be a pretty successful economy and a people who have a high degree of self-determination. But understand, for China, the issue of Taiwan is as important as anything on their docket. The idea of one China is at the heart of their conception as a nation.”

Yang says that Trump’ selection of a longtime associate of Xi as U.S. ambassador to China, Iowa governor Terry Branstad, further shows Trump is preparing for a tense relationship with China.

“That is why he picks Xi Jinping’s friend; because he wants balance. He wants to put a break there. You fix your breaks so carefully, because you want to drive fast. Otherwise, there is no such need.”

Yang, conceding he remains “very cautious.”

Still, he is hopeful the Trump administration will be willing to tackle the “inconvenient” problems posed by human rights abuses in China and the “unfair” international isolation imposed on Taiwan.

“The 40-year equilibrium is very stable. That means if there is a perturbation, the trajectory can go out of orbit very suddenly,” Yang says. “Now, people on Trump’s team may not be in the mainstream but they want to do this inconvenient job. I really appreciate that.”

He knows that the Tsai phone call, the television interview where Trump questioned the value of the “one-China” policy and the flurry of Tweets may amount to nothing, but he is still optimistic.

“I want them to be consistent: back up what they are doing with a long-term value-based plan,” Yang says. “If Trump has a backup plan, then he is a game changer.”

|

|

Chairman of the Norwegian Nobel Committee Thorbjoern Jagland poses next to the Nobel diploma and Nobel medal placed on the empty chair during the ceremony in Oslo City Hall Friday Dec. 10, 2010 to honour in absentia the Nobel Peace Prize winner, jailed Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo. (AP Photo Heiko Junge, pool)

|

Editor: Olivia Yang

Source: https://international.thenewslens.com/article/57908