By Yang Jianli

(English Translation)

We cannot blame people for being unable to resist cheap goods. But it is a different story when it comes with a price. The fact is everything has a price.

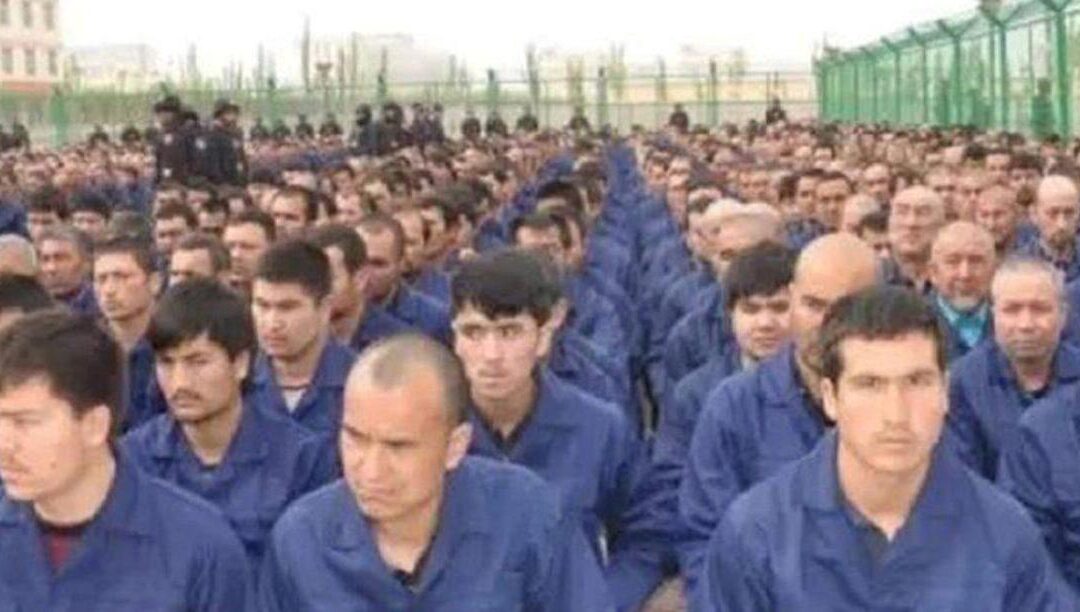

Over the past three decades, consumers in developed democracies, Germany included, have been enjoying relatively inexpensive products made by cheap laborers in other parts of the world, such as China. These countries have gradually maneuvered themselves into a position where they cannot produce their own headphones or toys at reasonable costs. Yes, cheap labor. In many cases, they are as cheap as in zero, because of forced labor. That is something you may call the price of freedom.

According to a study by our organization (https://www.citizenpress.com/

Consumers in developed democracies unknowingly become enablers of the perpetration committed by world’s leading human rights violators like China. This should go against their conscience because it runs against the very values these democratic citizens uphold as their guidelines of everyday lives and the foundation for their country. Moreover, in a long run, they may offer a rope with which to hang themselves. China, with the economic power built mainly through taking advantage of the markets in developed democracies, has made inroads in these countries’ businesses, politics, media, academia, entertainment, technology and even national security, undermining their democratic way of life. Relying too much on China’s supply chains, for example, as the coronavirus pandemic has exposed, for their basic needs would put them at the mercy of China when such a crisis takes place. These would be the prices they would have to pay if they allowed this to continue.

Yet, too many of our eyes have adjusted to the shadows that power and greed cast on the existence of the world citizens around the globe. Now we are in the shadowy valley of our times, to summon the wisdom and the best heritage of mankind and remind ourselves that each one of us has an opportunity to act in a way worthy of the best of our humanity. The other option is to adjust our eyes to the shadows. But friends, I have seen firsthand what takes place in these shadows.

I was born three years before the Cultural Revolution. At an early age, the unspeakable sufferings that most families had at the hands of the Communist dictatorship, including mine, made me disenchanted with the Communist party. However, I was enticed into joining the party with the idea of reforming it from within. This all changed when I returned from my Ph.D. studies in the United States, to join thousands of my fellow students in Beijing as Chinese army tanks rolled across Tiananmen Square on the morning of June 4, 1989. Luckier than most of my fellow students, I narrowly escaped the massacre and the ensuing arrests and returned to the United States. While I continued my studies, I immersed myself in the work advancing human rights and democracy in China. In the Party’s eyes, the former young Communist star had now become a public enemy. I became persona non grata, a traitor, prohibited from entering the country. But in the spring of 2002, I decided to defy the ban. In China’s industrial northeast, thousands of workers were taking to the streets, protesting the destitution brought on by government policies. Sensing an opportunity to forge bonds between democracy leaders and grass roots activists, I smuggled myself into China.

For two weeks I met with exploited construction laborers, expropriated farmers, and striking workers, documenting their grievances and the condition of their lives and helping them with non-violent struggle strategies. But as I attempted to slip out of China across the Burmese border, I found myself in the hands of the security police.

I was detained for five years. Much of those years I spent in solitary confinement. My mental condition deteriorated beneath endless isolation, repeated interrogations and ongoing psychological and physical torture. I resorted to composing poems in my head and committing them to memory as a means of maintaining my sanity. Nearing a breakdown, I grasped onto my innermost resources of imagination, belief, and will to fend off insanity and find a reason to live. “Am I wrong?” I asked myself with a tinge of regret. But I repeated a thought experiment: imagining of myself taking a copy of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, arbitrarily choosing any one on the Chinese street, showing the document, asking them with the language they understand whether they want the rights listed there, which are enjoyed by people in the free world. Would anybody say No? Of course, Not. Nobody wants to be a slave. In this regard, the Chinese people are no different than any other people in the world. The thirst for freedom and dignity is indeed universal. I drew strength and inspiration from this first order of fact.

I also thought of my fallen brothers and sisters in Tiananmen Square. I reassured myself that freedom is not free. Freedom must be earned. It was not free for those who paid with their lives. It is certainly not free for those of us who, while still blessed with our lives, have yet to complete the mission for which these brave students gave their lives and their freedom. I must not give up! This the price of freedom I must pay.

As we consume the cheap goods made in China, are they really cheap or we are paying a hidden price of freedom? Are we enabling the dictatorships in their atrocities against human rights, or we are helping those who struggle hard to achieve democracy as we are enjoying? Are we owing them sympathy and solidarity? Consumers of developed democracies must be alert to these questions.