Citizen Power Initiatives for China | Aug 24, 2022

Background

Under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) regime, China’s government has implemented various family planning policies for generations, starting with the one-child policy introduced in 1980—which remained in effect until 2015, when a two-child limit was established. These strict birth restriction policies were largely “successful” owing to their tyrannical enforcement: Violators were subject to an array of punishments, including hefty fines and even loss of employment. In May 2021, the regulation was loosened to a three-child limit; and in July 2021, all limits and all penalties were removed. This is no coincidence. Over the past year or two, the top leadership has found that China’s population growth is too low to support continued and sustained economic development. Therefore, the CCP took a sharp turn and implemented a policy under which births are now promoted with great fanfare. For instance, last year, the government of Feng County, in China’s Jiangsu province, publicly commended a man named Dong Zhimin: a purported “heroic father” of eight children in Dongji Village, a small community in the county’s Huankou Town. Government officials quickly organized a group of Internet bloggers with “positive energy” to promote Mr. Dong’s good deeds and the praiseworthy spirit of “a father with love like a mountain.”

On January 27, 2022, a man named “Brother Xuzhou Yixiu” posted a video shot at Mr. Dong’s residence on the video-sharing platform TikTok (known in China as Douyin). In the footage, Dong can be seen dressing and feeding the children while his wife is shackled to an iron chain around her neck, wearing tattered clothes and shivering in near-freezing temperatures in a dilapidated hut. Several of her teeth were missing, and the food in front of her looked like dog food. The video was posted and shared online and quickly went viral. This is how the case of the “Chained Woman” of Feng County came to be so well known.

Cause of the incident

(a) Long-term repercussions of China’s family planning policy

According to the United Nations (UN), the expected male-female birth ratio is 103-107 males to 100 females. The family planning policy implemented by the CCP for many years caused a severe imbalance in the ratio of males and females in rural areas. As a result, many village dwellers bribed medical personnel to reveal the sex of their unborn child, and aborted the fetus when it was found to be a girl. The male-female sex ratio thus became significantly unbalanced. According to data released by the CCP, the ratio of men to women in the 20-29 age group reached a peak of 121 males to 100 females in 2004. By 2019, the ratio was down to 110 to 100, which still meant that men outnumbered women by nearly 30 million. Rural women of marriageable age often move to urban and wealthy regions, leaving men in impoverished rural areas without women to marry. This has generated a huge demand among single men to “buy” wives, leading to the widespread practice of trafficking women in rural China.

(b) Trafficking of women has become a widespread crime tolerated by all tiers of government, from local CCP officials all the way to the provincial and state level.

The CCP has always ignored human rights, especially women’s rights, which are often violated with impunity. This is the deep-rooted reason for the rampant trafficking of girls and women in Xuzhou and other regions of mainland China that occurs today. The countryside’s intelligentsia have moved to the cities, causing morality to deteriorate in rural China. China’s remote villages and rural countryside have long been regions of interest for human traffickers. This is evident from several known cases of abduction and trafficking of women and children. In one case, after an abducted woman managed to escape, all the villagers chased after her and assaulted her. The woman was trampled and tortured in broad daylight, but her neighbors turned a blind eye. In fact, when it comes to the abduction and trafficking of women and children, China’s rural regions have become “communal accomplices”, with villages, townships, and even county-level CCP officials complicit in these heinous crimes.

(c) Higher-level governments ignore, obscure, or even glorify human trafficking.

Not only are small local governments guilty of inaction, but so is China’s entire judicial system. The holds true for county-level and provincial governments, and even the national government. After news about the case of the “Chained Woman” went viral across China (and even around the world), five investigative reports were issued by several of the municipalities involved, but the reports blatantly contradicted each other. Nevertheless, state-level prosecutors and law enforcement officials did not take any punitive action against officials whose malfeasance and crimes were exposed in the incident. On the contrary, governments at all levels in Jiangsu Province openly blocked, detained and assaulted concerned netizens and citizen-journalists who simply wanted to know the truth. State-level security agencies interrogated and threatened netizens who gathered online and urged an investigation into the matter. The case of the “Chained Woman” of Feng County is by no means unique. As it turns out, the Chinese government handles virtually all cases of human trafficking in the same way: quell the story, with force if deemed necessary, and punish ordinary citizens for asking the “wrong” questions or criticizing the government. Otherwise, this phenomenon would not be nearly as widespread. Regarding the tragedy of the “Chained Woman,” the CCP’s propaganda machine whitewashed all criminal activity—and there were obviously multiple crimes—related to the case.

In fact, the mainstream film The Story of An Abducted Woman (the Chinese title can be translated as “The Woman Who Married the Mountain”), produced by Changchun Film Studio in 2009, was adapted from a real case. The one glaring difference is that, in the movie, the man’s illegal purchase of his wife is depicted as a “heroic” rescue. And when the husband rapes his defenseless wife, whom he “purchased” from depraved traffickers, he is portrayed as “falling in love” with the girl. Clearly, the goal of the film studio was neither to condemn the rampant abduction and trafficking of women in China, nor to urge the audience to engage in introspection and rethink their moral obligations. Quite the opposite. The film actually encourages these young female victims to accept their tragic fate, remain in the village where they were trafficked and sold, and devote the remainder of their life to their “buyer” (the husband), his family, and the village at large. The film completely glosses over the cruelty and barbarism that human trafficking entails; instead, it romanticizes the plight of a woman who, without her input or consent, is coerced and sold into marriage.

Scale

The case of the “Chained Woman” in Xuzhou is not an isolated incident in China. Rather, it is just one instance of a common phenomenon with deep historical roots:

Vicious human trafficking (including violent hijacking, detention, rape, slavery, abuse, and even death) has been widespread in mainland China for many decades. In 1989, an investigative report called “Ancient Sins” was published. According to the report, at the time, more than 40 women were abducted and sold on average every day in the six counties of Xuzhou alone, and two-thirds of the wives in some villages were literally bought. In the 1980s, the media was more transparent. The northern Jiangsu region is not alone. Shandong, Anhui, Hubei, Shaanxi, Shanxi, Guangxi, Guizhou, Sichuan, Henan, Hebei and other provinces also have a large number of trafficked women. They come from all over the country, including Shanghai and Beijing, the safest and most developed regions of China, from underage girls to middle-aged wives, from village girls to college students, graduates with Master’s or Ph.D. degrees, returnees from overseas studies, and college faculties. In the 1990s, Jiangji Village, in Jiangsu Province’s Siyang County, was once the largest wholesale market for trafficked women in northern Jiangsu.

According to the “China Action Plan Against Trafficking Women and Children (2008-2012)”, in the short span of around one and a half years (Apr2009 to Dec. 2010), 9,165 cases of abduction of women were prosecuted, and 9,388 children and 18,000 abducted and trafficked women were rescued. These numbers are probably significantly understated. But regardless of the precise figures, it is clear that every year, countless young girls are abducted by human traffickers and taken to China’s remote countryside, where they will endure a miserable existence, often for the remainder of their time in this world. The recent case of the “Chained Woman” is just one incident that happened to be uncovered and exposed before the news could be crushed by the heavy artillery fire of China’s censorship machine.

It is difficult to obtain accurate data on the number of trafficked women (including adult women and underage girls) across China. Zheng Tiantian, a professor of anthropology at the State University of New York, published an article in the Journal of Historical Archaeology & Anthropological Sciences in 2018. According to the statistics of international organizations, from 2000 through 2013, the total number of young women and children trafficked in China was 92,851. But Professor Zheng emphasized that the actual number of trafficking victims is probably much higher than that. In her research, she found that the abducted women are predominantly from the provinces of Anhui, Guizhou, Henan, Sichuan and Yunnan; and they are trafficked to relatively impoverished rural regions such as Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Shandong, Henan and Inner Mongolia.

It appears that the Chinese government’s data on human trafficking are “top-secret”. According to a U.S. State Department’s report issued in 2021, this is the fourth year in a row that the Chinese government has failed to release any data on victims of human trafficking.

Why does trafficking of women keep going?

(a) The serious imbalance in the male-to-female population in rural areas caused by decades of family planning policies cannot be resolved in a short period of time. At present, there are 34.9 million more men in China than women. Among the population who have reached marriage and childbearing age, an average of 1 in 5 men will be unable to find a wife.

(b) Local governments, police, human traffickers and villagers are the four critical components of the criminal chain, and, of course, they are also the beneficiaries.

Since the mid-1980s, human trafficking has achieved a scale effect, and many government employees have become part of the chain of interest in trafficking. According to research, in 2018, the price of buying a kidnapped woman ranged from 6,000 to 40,000 yuan (USD $900 to $6,000). The villagers treat the abductee as their own private property and form a common criminal group to prevent the abducted women from escaping. The identities of many victims are difficult to identify and therefore difficult to be counted. After since many abducted women were registered with local hukou (a residential registration system), their identities could not be confirmed and they were never rescued. The local-level police bureaus in rural areas are severely understaffed, and cracking down on human trafficking is not included as part of the evaluation process.

Judicial handling of trafficking cases is also subject to local protectionism. Civilian forces do not have the power to enforce the law. Most of the police stations with the power to enforce the law are reluctant to do anything. The rescue can only rely on the government, but most of the time, the government stands with local protectionism. The local government departments not only do not combat trafficking, but also do not support the rescue of victims, and sometimes even obstruct the rescue of victims.

Che Hao, a professor of criminal law at Peking University, published an article in the academic journal China Law Review in February, pointing out, “In the face of peasants who just want to buy a wife, we can count on local law enforcement who live in the same area historically and culturally with the traffickers. It can only be a beautiful ideal to expect those law enforcement personnel to go hard after the abductors.” He emphasized that the buyer may be a member of a social network of local acquaintances, and investigators have a strong justice motivation to rule on the buyer’s rape, detention and other serious crimes. A light crime of transaction is often charged, and a probationary sentence follows.

(c) If abducted women are abused and imprisoned for many years, it is very likely that they will suffer from mental disorder and Stockholm syndrome, and choose not to leave the “family.”

(d) The squire culture has been eliminated, and ethics and morality have been severely damaged. In the past squire culture, in the clan society, marriage was the best way to bond two surnames, and it was the link between two major families. In this social structure, a bought stranger could not be admitted into the community. However, this elimination of this culture after 1949 brought problems to rural governance. Now rural governance relies on institutions such as the village committee and village CCP branches. Ethics and morals cannot reach the hearts of ordinary people. There is a negative correlation between the severity of human trafficking in various parts of China and the strength of local clan culture. At present, where human trafficking is more serious, such as Shandong and Henan provinces, their clan bond is relatively weak; in places with strong clan link, such as Guangdong, Guangxi and Hunan, human trafficking is relatively rare.

(e) The rescue actions of civil organizations at grassroots or upper levels, especially of women’s rights groups, were suppressed instead.

Since 2012, some civil rights organizations, such as China Women’s Rights, especially those with overseas backgrounds, have been severely suppressed by the government, and their role in women and children’s rights and other fields has been greatly reduced. From the case of the “Chained Woman,” it is apparent that non-governmental organizations (NGOs) played no role in fighting for justice; rather, it was public concern (and even anger) expressed in the form of social media posts that exposed the case and caused it to go viral.

(f) The prevalence of abduction and trafficking reflects the festering of the system. The CCP regime, only caring about its own image and governance security, never has the motivation to uproot the problem; moreover, this kind of phenomenon is symbiotic with the characteristics of the CCP regime, and the CCP itself is powerless to eradicate the tumor.

What should the international community (UN, human rights groups and democratic governments) do?

(a) More support and give full play to the reporting and tracking of social media platforms.

(b) More support to civil organizations and join forces to rescue abducted women

(c) Call for the institutionalization of treatment and long-term care for the victims. The state has issued relevant policies and regulations to respect the choice of the victims and their families for their follow-up treatment and residing places. The local government where the family of the abductor is located has the responsibility to fund and make other arrangements to accept and properly treat and place victims. At the same time, a compensation law should be formulated to compel the perpetrator (both buyers and sellers) and the responsible person to pay a certain percentage of alimony.

(d) In addition to ensuring personal safety, assistance for the mental and psychological needs of the victims should be provided. After leaving the buyer’s family, the woman not only faces loneliness, but also their original family’s rejection. It is difficult to reorganize a family, and it is a painful experience to leave without the children. Through various social organizations to connect the victimized women, form groups, carry out activities, unite to tackle difficulties. Additionally, social organizations should provide opportunities to conduct interactions and help them rebuild their lives.

(e) Rural cultural construction should be promoted through various forms. Human abductions and trafficking should be condemned, and victims should be given respect and confidence to rebuild their lives. As previously mentioned, women who are victims of trafficking face are further victimized by the cultural discrimination they endure, and are either homeless or have no home. This malicious culture—in which criminals go unpunished and victims face discrimination—needs to be corrected, such as the movie The Story of An Abducted Woman that promotes misconceptions. The opposite case is South Korea’s Melting Pot, a movie based on the true incident of a deaf school principal who sexually abused children in Gwangju, South Korea in 2005. Because of its far-reaching influence, millions of netizens signed a petition to protest the original ruling, resulting in a retrial and a review of the Sexual Assault Prevention Amendment (aka the “Melting Pot Law”). This film changed South Korea for the better.

(f) Allocate substantial human and financial resources to conduct investigations into individual cases of human rights abuse in China. Call on the international community to pay closer attention to the human rights crisis in China. Strongly condemn and intervene in the Chinese government’s disregard for and violations of human rights.

Appendix

Summary of the “Chained Woman” Incident

Report by Citizen Power Initiatives for China

The “Chained Woman Incident” (also known as the “Xuzhou Eight-Child Mother Incident”) occurred in Huankou Town, Feng County, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province, China.

1. What happened

By late 2021, a story circulated locally about a 50-year-old father named Dong Zhimin who was raising eight children in Feng County. The news caught the attention of citizen-journalists, who visited the village and documented their findings. On the evening of January 27, 2022, Chinese blogger “Xuzhou Yixiu Ge” visited Mr. Dong’s residence and posted footage on the video-sharing platform Douyin. The video clip showed a mother of eight children with a chain around her neck in a dark, dilapidated hut. The temperature was very low at the time, and she was sitting on a tattered bed, dressed inadequately for the cold winter weather. There were a few moldy steamed buns scattered around. Reportedly, the woman had been locked up like this for more than 20 years, with rare exceptions, and she was forced to give birth to eight children in these inhumane living conditions. After the video was posted online, it was quickly shared and reposted by concerned Chinese netizens, who dubbed the woman the “Iron-Chained Woman of Feng County.” The public, worried that the victim had been abducted, trafficked and subjected to domestic violence, appealed to the police to intervene and confirm her true identity. Within days, angry Chinese citizens made condemned the woman’s mistreatment and called on the government to intervene. Several human right activists went to the village to investigate the matter, hoping to help the victimized woman. With growing appeals from the community for a thorough and credible independent investigation into the incident, the government finally had no choice but to respond.

2. The government’s series of responses

In its first report, the government of Feng County stated that the woman’s name was Yang X Xia, and claimed that no abduction or trafficking was involved. On January 28, 2022, the Propaganda Department of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) branch of Feng County issued an investigative report. According to the report, the woman who gave birth to eight children was named Yang X Xia. She married Dong Zhimin in August 1998, and there was no occurrence of abduction or trafficking. The report also quoted family members and neighbors as saying that Mrs. Yang often beat children and elderly people for no reason. She was diagnosed with mental illness and had been treated. The same day, an official with the local Propaganda Department told Jimu News that the online rumors that the woman had been abducted, trafficked and subjected to domestic violence were untrue. After the Feng County report was released, Chinese netizens had more questions than answers: Why hadn’t the woman’s family showed up if they lived in the same town? How could her parents tolerate their daughter suffering such abuse?

According to Feng County’s second report, the woman was tied to a chain to prevent her from “getting sick,” and no evidence of abduction or trafficking was found.

On January 30, the Feng County Joint Investigative Team issued another investigative report, claiming that the woman was “mentally handicapped.” According to the report, the “Iron-Chained Woman” was taken in by the Dong’s parents when she was begging and wandering the streets in June 1998, and the couple has lived together since then. The report further stated that she is still capable of taking care of herself. The report also claimed that the woman was chained because her condition had worsened since June 2021, adding that she often threw things and was shackled to prevent her from hurting others.

The Jan. 30 report proves that the earlier report that “Yang X Xia” was from the town is a lie. According to the video, some netizens found that with regard to her appearance, age, and accent, the woman could be Li Ying, who disappeared in Sichuan 26 years ago. There are even online posts mentioning that local officials first “conquered her virginity,” and the family members of those local officials were protesting. It also mentioned that several male members of the Dong family “shared” the woman. To prevent Li Ying from rebelliously biting at others, her front teeth were pulled out. Due to the contradictory official narrative and Feng County government’s lack of openness and transparency, public interest and concern continued to build.

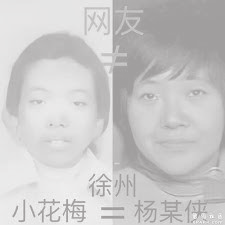

According to a third report by Xuzhou City (superior to Feng County in government rank), Yang X Xia’s name is Xiao Huamei. Because of her abnormal speech and behavior, her parents entrusted a fellow villager surnamed Sang to “take her to Jiangsu province for treatment and find a well-off family to marry.” She was lost in Jiangsu Province and her family members were never notified.

On February 7, the joint investigative team of Xuzhou City announced that the “Iron-Chained Woman” was Yang X Xia, formerly known as Xiao Huamei, was from Yagu Village, Zilijia Township, Fugong County, Yunnan Province. She married in Baoshan, Yunnan Province in 1994 and returned to Yagu Village after divorce in 1996. At that time, a woman surnamed Sang from the same village (who was married in Jiangsu Province’s Donghai County, adjacent to Feng County) was entrusted by the chained woman’s mother and took her to Donghai County for treatment. She was lost in the local area, but Sang neglected to call the police or inform her family. The investigative team stated that the chained woman had already shown abnormal speech and behavior when she was living in Yunnan Province’s Yagu Village. The investigative team called upon medical experts at the city and county levels to consult and provide treatment for the chained woman’s “schizophrenia,” and her condition was reportedly stable. The report mentioned that the chained woman’s tooth loss was the result of severe periodontal disease, and other health indicators were normal. The report also pointed out that after DNA identification by the Nanjing Medical University Forensic Institute, the eight children, Dong Zhimin and the chained woman were all in line with biological parent-child relationships.

In response to this report, former investigative reporters “Tie Mu” and “Ma Sa” of Yunnan Information News visited Yagu Village in Yunnan Province’s Fugong County. They learned that Xiao Huamei is indeed from Yagu Village and has a half-sister surnamed Guang; but no one— including the “sister”, neighbors and villagers—could recognize Xiao Huamei. Xiao Huamei, as mentioned in Xuzhou City’s official report, was only recognized by a drunk man; local villagers said the woman was of Lisu ethnicity, but the language spoken by the chained woman in the video was not the Lisu language or a similar dialect.

The third report proved that the claims of “vagrancy and begging” in the second report were likely untrue, and that it was more likely that the woman was a victim of human trafficking. As a result, voices of doubt on China’s heavily-censored internet grew even louder.

A fourth report issued by Xuzhou City admitted that the chained woman had indeed been abducted and sold, and that Dong was suspected of illegal detention. The report reiterated that the chained-up woman is Xiao Huamei.

On February 10, the joint investigative team of Xuzhou City issued their findings. The report stated that Dong Zhimin was suspected of illegal detention, and the woman surnamed Sang and her then-husband were suspected of abducting and trafficking women, and both were taken into police custody. The investigative team’s report further stated that after the police at all levels conducted DNA tests and comparative studies between the chained woman and her half-sister (surnamed Guang, formerly Hua) and the chained woman’s deceased mother (surnamed Pu), it was concluded that Pu was indeed the biological mother of the chained woman and Guang (supposedly her half-sister); and that the chained woman is Xiao Huamei.

However, netizens raised various doubts about the DNA comparison. They compared and posted photos of the two women and Xiao Huamei, photos of marriage certificates, photos of Li Ying and photos of Li Ying’s relatives, and believed that the chained woman was more likely to be Li Ying. The so-called tooth loss of the chained woman was also questioned by dental experts. And there was no explanation for the loss of the tip of her tongue.

On February 15, Deng Fei, a former editorial board member of Phoenix Weekly, posted on Weibo several wedding photos of Yang X Xia and Dong taken on August 2, 1998. The photos show a significant difference between the appearance and the “mother of eight children.” Deng Fei said that he received a photo of Yang X Xia and Dong Zhimin’s marriage certificate from netizens, showing that the two became officially married in August 1998, and Yang was born on June 6, 1969.

Jiangsu Province Investigation

According to a fifth report was issued by the provincial government of Jiangsu province, the chained woman was Xiao Huamei; she was abducted and sold to Dong Zhimin’s father, not a homeless person. Comparing the DNA of Li Ying’s mother and Yang X Xia, it is evident that the two are not the same person. Dong Zhimin was arrested on suspicion of abuse. Those involved in the abduction were all arrested. All 14 Feng County officials were expelled from the CCP and dismissed from their posts.

On February 17, the Jiangsu provincial government and the province’s CCP branch set up a team to investigate the incident of the “Feng County woman who gave birth to eight children.” On the morning of February 23, the provincial investigative team released a report on their investigation. Echoing the findings of the fourth report issued by Xuzhou City, it confirmed that the chained woman is indeed Xiao Huamei. It also confirmed that she was abducted and sold to Dong Zhimin’s father, instead of a homeless person.

Regarding the online rumor that Yang X Xia is Li Ying—a missing woman from Sichuan—the report said that public security agencies compared the DNA of Li Ying’s mother and Yang X Xia, and the results showed that there was no biological parent-child relationship.

In terms of crimes and punishment, the report pointed out that since 2017, Dong had carried out abusive acts such as tying Yang X Xia with cloth ropes, chaining her neck, and not sending her to a doctor for treatment when he fell ill. A warrant for his arrest was issued on February 22, and the relevant public security agencies will carry out an investigation and collect evidence. Warrants for the arrest of the woman surnamed Sang and her husband, who participated in the abduction and trafficking of women, were also issued, and the other six suspects were all placed under detention by the police.

The report announced the charges of the concerned persons and the arrest of Dong Zhimin for abuse, adding that the investigation and evidence collection process will continue. In addition, Feng County CCP chief Lou Hai, county head Zheng Chunwei, propaganda director Subei and three other high-level party and government officials who concealed the incident and released false information, were dismissed from office. The three colleagues, including county vice chief, the director of public security, the CCP head of Huankou Town and the town’s mayor, and 14 other officials were all expelled from the CCP and dismissed from their posts.

3. The Chinese government’s corresponding silence and arrest

When the incident first occurred, online comments about the case were rarely censored and limited arrests were made in Feng County and Xuzhou City. Therefore, the public’s online outcry reached a climax due to a lack of social media account suspensions. However, after the release of Jiangsu province’s investigative report, related social media posts were deleted and, in some cases, users had their accounts suspended.

The incident about the “chained woman” has attracted the attention of as many as 100 million Chinese netizens, setting a new record for the number of netizens paying attention to issues of social welfare. Netizens across China have been scrutinizing the fairness and handling of the “chained woman” incident. Citizens’ use of the internet to monitor public power and force the government to take action is something that had never happened before in China’s 70-plus year history.

On February 18, two female netizens with the online names “I can hold 120 jin (60 kg)” (hinting at Xi’s boast that he carried 200 jin and climbed 5 kilometers without switching shoulders) and “Sister Xiaomeng Xiaoquanquan” wrote a post on Weibo about what happened to them on their way to Feng County to visit the chained woman. The two went to the Second People’s Hospital of Feng County together on February 10, hoping to send flowers to the chained woman, but they were obstructed and their mobile phones were seized by officials. Later, they received a warning from the police. On the evening of February 11, they were arrested. Police from Feng County’s Sunlou subdistrict detained them on charges of “stirring up instability and trouble” and the two were aggressively interrogated, abused and beaten. The two netizens were released a few days later, but in early March, the family of “I can carry 120 jin,” said that they were detained by the police again. Later, the family learned that the two women had been placed under house arrest in Pei County, Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province. They were actually forced to disappear from public view.

In addition, some netizens tried to visit the chained woman in Dongji Village, Feng County, but they were blocked by the police. According to a senior media executive, the authorities blocked traffic into Dongji Village, Feng County, where the incident occurred, and prohibited reporters from approaching the public, citing pandemic control. Militia forces were stationed at the village entrance.

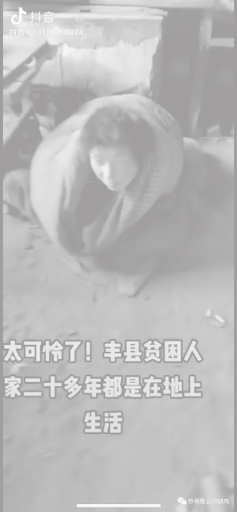

At the end of January, not long after news of the chained woman came to light, a video of another woman lying on the ground in the same village as the chained woman for more than 20 years also appeared on the internet, but it was quickly deleted. The woman has reportedly been living on the ground for more than 20 years, wearing only a quilt. She doesn’t speak and can only scream at the camera.

On March 1, another netizen posted a photo of a caged woman in Shaanxi Province’s Jiaxian County, and the photo was even more horrifying. The local public security bureau in Yulin City announced their investigative results on April 6, downplaying the incident.

4. Follow-Up

On January 28, 2022, the local health department sent the chained woman to the Psychiatry Department of Feng County Second People’s Hospital. Two days later, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia and periodontitis by medical experts in Xuzhou City. Nanjing Brain Hospital confirmed the diagnosis. According to one official, Xiao Huamei was looked after by her eldest son Dong X Gang and the hospital’s medical staff. The chained woman has been moved out of Feng County, and her specific whereabouts are unknown.

The other six minor children (there are seven minor children, but only six appear in the video) stayed in Dongji Village and were taken care of by Dong Zhimin’s mother and other villagers. The two huts where the woman kept in chains have been demolished.

Society’s Reflection

Aside from the issuance of official reports (which have been proved uncredible), almost no official media in China reported about the case. In China, “the threshold is getting higher and higher” for a social incident to attract attention. So why did the chained woman incident gain so much public attention, despite the government’s attempts to suppress their voices, even causing the public to investigate the case spontaneously? Primarily, it is because of the “extremely cruel and inhumane experience” of a mother of eight children, arousing a great deal of empathy. The Xiao Huamei incident has been deemed a “tipping point” for average Chinese citizens to speak out in an Orwellian society where speech is routinely suppressed. Although the incident itself is so radical, many people feel it has happened to themselves.” Although they may not be women living at the bottom of society, or might not experience the similar mistreatment, “this incident revealed the reality that “though it is peaceful and good on the surface, a lack of security is entrenched. Chinese women’s sense of security in their daily life is extremely low, and in the face of the threat of violence, security gave way. Many women shared their dangerous experiences of being abducted and trafficked online, lamenting that “the distance between me and the chained woman may be just a stick strike.”

It is worth noting that State Council premier Li Keqiang has stated that China will carry out a severe crackdown on the trafficking of women and children. But under the CCP’s policy of “stability above all,” it is unlikely that the truth of the chained woman will ever be known by the general public.

The incident of the “chained woman” has caused shock and anger, but it is only the tip of the iceberg of the trafficking of women in rural China. A reporter interviewed abducted and trafficked women in remote mountain villages, and learned that up to 50 percent of husbands “bought” their wife. According to our sources, in the hands of human traffickers, the women who were abducted and trafficked were routinely detained, raped and tortured, so they were eager to escape their traffickers even if it meant being “sold.” Some of them are even grateful to the buyer for freeing her from the devil. It is not surprising that officials at all levels (Feng County, Xuzhou City, and later Jiangsu Province) have concealed and defended cases of abduction and trafficking. Everyone knows who bought a wife, but officials, especially local officials, have never taken the initiative to confirm the existence of human trafficking; on the contrary, they actively participate in and maintain the human trafficking network. In other words, there is a tight network of human trafficking throughout China. The trafficking process begins with deceiving the victims, through the whole process of abduction, trafficking and trading, and finally molding them into so-called “family members.” Such an operation could not continue without involvement of the government and police. In the end, the women cannot escape this network. Some victims have been trapped in this network for decades, or even their entire lives. Their fates are largely determined by the government. The police do not rescue them, the courts do not grant a divorce, but the government is willing to issue them a marriage certificate.

While serving as deputy editor-in-chief of the Southern Metropolis Weekly in 2006, I sent reporters to investigate cases of missing children across the country. We found that there are thousands of cases of missing children reported in China every year, but the police do not investigate the vast majority of cases and refuse to provide surveillance video. Now, more than 15 years later, China’s surveillance technology has become exponentially more developed, with surveillance cameras everywhere, but cases of missing children and abducted women are still a daily occurrence.

However, if a concerned citizen reports a case, the police will still claim, “We’re too understaffed to provide surveillance video.” In one case from over a decade ago, a child was abducted by one of his aunts. With surveillance cameras on the street corner where the abduction occurred. The police could have immediately found the trafficker and rescued the child if they viewed the surveillance footage. However, more than ten years, the child is still missing, despite efforts by the entire family to find her.

Although officials have the capability to investigate such cases, they are unwilling to do so. Why does the government allow the abduction and trafficking of women and children? Because the commodification and instrumentalization of women and the disregard for the basic rights of women and children are inherent in a patriarchal, totalitarian society.

Regarding the chained-woman incident, how can village officials, Women’s Federation personnel and the police feign ignorance and refuse to speak out? Do they dare to claim that no violations of the law have occurred?

Should no one other than the traffickers and buyers be held responsible in such cases of human trafficking?

According to official reports, tens of thousands of local women have been abducted and sold. How did these abducted women get their marriage certificates? How does the child born by such a woman obtain a legal identity and hukou (household registration)? Isn’t there a complete criminal enterprise behind it?

Shouldn’t there be concerned departments to take responsibility?

In fact, local villagers and grassroots officials alike are crystal clear about what is happening—but they choose indifference over compassion, and ignorance over awareness.

As mentioned in a previous Citizen Power Initiatives article, the abduction of women will inevitably lead to the demise of the entire village. Because in a case such as that of the chained woman, society has been stripped of its moral values and degenerated into a self-perpetuating state of barbarism.

The essence of human civilization is that people have unalienable rights, including “the right to life, liberty and security of person.” All collectivism and narrow-minded nationalism should die out if it comes at the expense of people’s basic rights and free will.

For barbarism and ignorance, education is only one aspect, and more important is severe punishment. The criminal act of buying and selling people, both the seller and the buyer, must be severely punished.

In reality, the case of Xiao Huamei is not unique. Her fate reflects the fundamental and undeniable lack of justice, especially for women, in Chinese society.

Only in a society that supports justice, and in which people are willing and able to speak out against injustice without fear of reprisal, can parents stop worrying about their children.

In the fifth official report, it is notable that the victim is called the “woman with eight children in Feng County”—instead of the “chained woman,” as she is often referred to by the public. This is no coincidence. Clearly, the CCP is trying to portray the incident as an internal “family conflict” in which the chained woman is simply the mother of many children. Also noteworthy is the fact that the report highlights the word “family,” which can be interpreted as encompassing the woman’s extended family and any domestic abuse that occurring within. Thus, serious criminal charges such as abduction, rape, or illegal imprisonment cannot be pursued.

Numerous legal documents could previously be found online related to cases of abducted women in mainland China who have filed for divorce. However, the CCP and of China’s state-directed censors have since purged these documents, or restricted access to them via the Great Firewall, which blocks access to tens of thousands of websites. According to online posts, Chinese courts even went as far as issuing a warning to remove any legal documents related to abduction or trafficking from the internet.

It is obvious, therefore, that despite the large number of cases of women being abducted and trafficked in China, the judicial system cares only about protecting the interests of the abductors and traffickers. Women who apply for divorce are identified as “family members,” and their cases are treated as “internal” family issues. In theory, these maltreated women who have been sold into marriage can file for divorce. One lawyer, who spoke on condition of anonymity for personal security reasons, examined 245 divorce rulings in cases of abducted women in China. He found that it is extremely difficult for such victims to be granted divorce. Hence, as he notes, trafficked women who seek divorce after being sold into a forced marriage face an uphill battle—even if they have been held in captivity and subjected to rape and physical abuse. This point is important, and consistent with the narrative in the aforementioned government reports.

The lawyer added that these rulings rarely reflect the laws as they officially exist on the books. For example, the Marriage Law of the People’s Republic of China includes the following relevant clauses (bold added for emphasis):

- “The marriage system [is] based on the free choice of partners.”

- “Marriage must be based upon the complete willingness of the two parties.”

- “Marriage upon arbitrary decision by any third party, mercenary marriage and any other acts of interference in the freedom of marriage are prohibited.”

- “The exaction of money or gifts in connection with marriage is prohibited.”

Why, then, is there such a fundamental discrepancy between the laws and their implementation? Many judges in China are highly intelligent and have received top-tier legal education. Furthermore, many of China’s laws are formulated in the spirit of modern legal principles. The fact that Chinese women who are trafficked and sold into marriage rarely have any feasible legal recourse can be partly attributed to the indolence, indifference or moral cowardice of a handful of negligent judges. But the majority of the blame for the gross mishandling of these heartbreaking cases reflects, directly or indirectly, the totalitarian CCP regime’s wanton disregard for the rights of women in China’s patriarchal society.